This is a bit of a shift from the typical format of this substack, but I’ve gotten numerous questions asking for a quick and accessible survey of Georgism, and this seems like the best platform to create it. I’m sure others have done the same, and better, but perhaps my take will hit a ‘sweet spot’ for people who enjoy my writing and want my specific perspective. I’ll try to stick entirely to Henry George’s own writings, not those of his subsequent followers (even if in many cases those individuals were more influential than George himself). I’ve tried to divide it into a few digestible principles.

George advanced a three-factor model of political economy

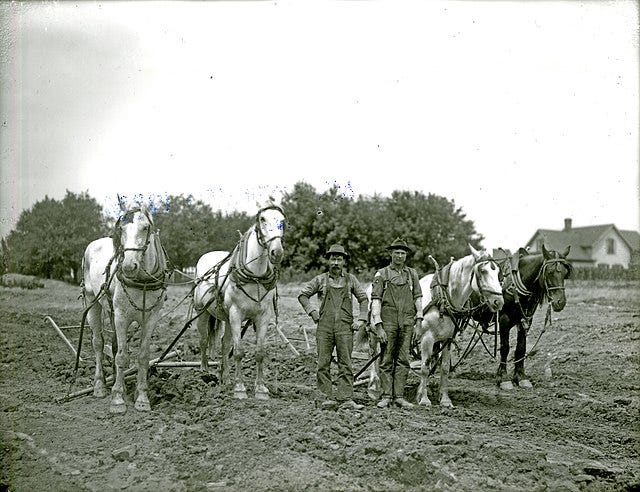

George’s vision of political economy grew out of older English Liberals, and he broke down the economy into three factors: Land, labor, and capital. Land refers to the natural universe, unimpacted by human actions. Labor is human action, and capital is any property used to increase the productivity of the interactions between humans and land. My colleague (a trained chemist) Mihali Felipe has broken down the idea of labor in terms of reducing entropy, and wealth in terms of objects preserving this reduction.

In turn, there are three categories of payments one can receive (either explicitly or implicitly) – wages derived from labor, interest drawn from capital, or rents derived from some legal right to land (or some other naturally or artificially scarce resource).

George believed in the potential for increasing productivity

Unlike many English liberals, however, George did not agree with Malthus’s position on population, which held that rising populations must always put greater strain on food sources until finally the population growth results in privation. Instead, he systematically found that in places where famine in his day was blamed on high populations – Ireland, India, and China – that in fact the result was the maldistribution of purchasing power and underinvestment in agriculture due to poor political economy.

As a result, he dismissed this explanation for poverty. Moreover, he believed the reason was not a worsening of human quality (nor was rising productivity related to an increase in the fitness of certain races, as many eugenicists claimed), and instead looked to the three factor model of production. George hypothesized that despite more wealth being generated, in most societies a smaller portion was being dedicated to wages.

George saw land as monopolizing this wealth

Looking at these factors of production and the payments from each, George concluded that wages and interest were determined not just by their productivity but by their scarcity. As society became more populated and wealthier, overall productivity would rise but the bargaining power of labor and capital would not necessarily rise with it – thus, rents would collect more and more of the wealth generated by society.

George used the population boom in the West as an example. Though California was not highly productive in the mid-1800s, it attracted hundreds of thousands of men looking for higher wages than they could get on the East Coast. As construction of more capital and the agglomeration of workers allowed for more specialization, the overall productivity – what we would call GDP per capita – of the state rose, but real wages didn’t seem to. Instead, because much of that prosperity required the use of very specific pieces of land, most of the new productivity went to paying landowners, mine owners, holders of railway right of way, and the like.

George believed capital also struggled in conflict with land

One reason the division between capital and land is so important in George’s work is that George generally identifies wages and what he terms interest (the returns on capital investment) as moving in the same direction, and both being crowded out together by land factor payments (rent). Just as the individual laborer found his wages failing to keep up with rent as land values rose, so too those who held only capital would see the profitability of their capital fall. A greater availability of labor means a rising investment in capital produced by labor – but does not generally alter the availability of land. Thus, the bargaining position of capitalists relative to landholders diminishes as overall capital stock increases.

This is why – though he was a union member himself and drew much of his support from unions – George did not see industrial striking and labor action as likely road to higher wages. Only by diverting the rents on land could labor see wages rise consistently, and this was very difficult to do via strike, because labor had a much harder time feeding itself without working than land had maintaining itself without laborers.

This inequality was, for George, the source of most social problems

George identified many ills in the landowning system. In urban areas, he saw that those who did not own property were frequently pushed to the edges of society and resorted to crime to support themselves. In rural areas, the inequality of land ownership created a class of landless laborers who were both less wealthy than the landowners and, in George’s view, less invested in the well being of the country as a whole.

In a democracy, the insufficiency of land wealth redistribution further encouraged poor economic policies. George was an opponent of tariffs and proponent of free trade, but recognized that in the absence of land rent redistribution, laborers might rationally aim for a poorer, less efficient society if that inefficiency showed up in greater work availability. He went so far as to argue that militarism and imperialism were also largely encouraged by the landowning system, as imperial conquests allowed foreign landowners to collect rents on ever wider areas.

This does not mean George didn’t see any other problems in society – municipal corruption and police brutality, for example, were topics he addressed in his own mayoral campaigns for New York – but he believed that land rents were the ‘final robber’ that would continue to impoverish society no matter what other improvements were made.

Thus, George looked to the tax system for a solution

The solution, as George saw it, was to tax the value of land to fund government programs. This would both take the burden of taxation off of labor and capital (increasing real wages and spurring investment) and reduce the desirability of land holding for speculation, opening more land to use.

A key portion of this idea was that it had to be assessed on land values based on the potential – not actual – rent. Plenty of lots were and are held for directly capturing rent – speculation on rising prices or a to capture present high rents. However, many are also held to generate indirect revenues or simply private enjoyment. A massive golf course in a city or a lakeside vacation home may not on paper yield the rent the land is capable of generating, but they do prevent the use of the land for those more productive purposes.

George defended this system on two grounds – efficiency and fairness. Land value taxes are efficient according to classical economics because the quantity of land is basically fixed. While taxes on labor may diminish the workers’ desire to work, and taxes on capital may diminish investment in more capital, taxes on the unimproved value land cannot effectively reduce the quantity of land available. As an economist would say, there is no deadweight loss.

But George also held that this system of taxation was also fair (indeed, what he saw as the coincidence of justice and efficiency would come to a sort of spiritual belief for him). The labor of an individual was, as liberals since Locke had held, an extension of that individual’s self. That labor applied to created capital similarly was property held in all fairness by the person who made it, or the person to whom its creator sold it. But land, since it was not created by any kind of labor, could not be justly ‘owned’ in the same sense as other property, under the kinds of property rights Locke defended (indeed, Locke himself conceded that land could be owned by virtue of homesteading only so long as there was ‘as much, and as good’ left for future homesteaders.

George did not see the dissolution of capital as necessary but saw a larger future for socialized enterprises

Unlike Karl Marx, who was George’s near-contemporary, George did not see a need to dissolve capital, and did not find a meaningful distinction between ‘wealth’ and ‘capital’ (or ‘personal’ and ‘private’ property). For him, a factory could be justly owned by an individual or firm, because its profit margins could be controlled through competition by other factories – provided it was not possible to monopolize the resources needed (hence his opposition to tariffs and government rent seeking as well).

However, George did observe that a greater portion of the economy was being taken over by industries that lent themselves to monopoly. Transportation (especially railroads and streetcars), power generation, and communications (particularly telegraph wires) all lent themselves to becoming natural monopolies for reasons easily describable by classical economics. Additionally, George recognized that all these distribution networks effectively necessitated rights-of-way that were difficult or impossible to compete with due to their reliance on land rights. Thus, George supported the creation of publicly owned operations in their areas, and predicted that the advancement of technology would broaden the areas where social control was necessary.

Taxation, not revolution, was George’s remedy

George disagreed with both anarchists and communists who were his contemporaries in his belief that, at least in a democratic society, the key economic problems (especially land ownership) could be resolved via democratic and, in effect, fiscal means.

This isn’t to say that George opposed revolution methods in call cases – particularly in discussing the case of imperialized people, he showed sympathy for even violent revolution. And his preference for taxation over redistribution was based not on an ideological belief that land could not be justly redistributed, but rather that it was unwise to do so, because it placed too much power in the hands of state redistributors who were likely to use it corruptly.

George has been broadly interpreted by many different political interests

That was an interesting piece. I never dived much into Georgism before so it was nice to get an overview.

In your view, what are the strongest rebuttals? The logic seems sound, but it also has a lot of assumptions, and I wonder if the empirical expectations implied by his thinking consistently line up with what we see in reality.

The most telling fact is that the idea is firmly outside the overton window both of the mainstream and the alternative sectors. The history of the idea is infused with this realisation.