Buy (North) American

Needlessly alienating Canada and Mexico is poor economics and poor politics

It seems the only way to get any kind of major project passed in the US congress is to add to it layers of stipulations - and one of the most popular is ‘Made in America’ requirements. This has especially been true of major components of signature bills signed into law by Joe Biden - everything from electric vehicle subsidies to infrastructure spending contains provisions specifying that they are to benefit American producers. This broadly flies in the face of liberal trade logic, and has several practical downsides. The most common defenses - both economic and strategic - may have some merit, but are easily overcome with compromise: the expansion of Buy America provisions to include the entirety of North America.

An old debate

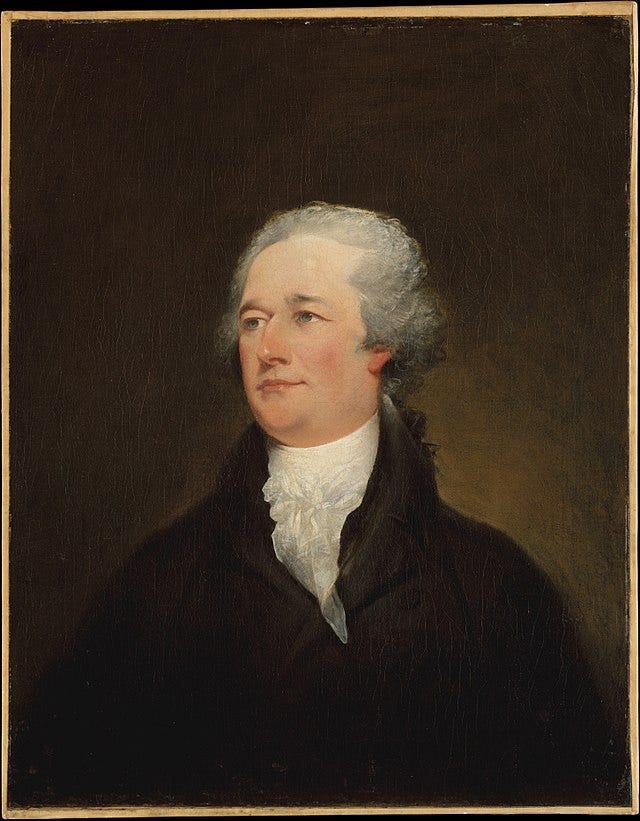

The debate over American trade policy is, of course, as old as America itself. It was an early conflict between Hamilton’s economic vision and that of Jefferson; indeed, in his Report on Manufactures, Hamilton gives a useful summary of the key argument against his position:

“If contrary to the natural course of things, an unseasonable and premature spring can be given to certain fabrics, by heavy duties, prohibitions, bounties, or by other forced expedients; this will only be to sacrifice the interests of the community to those of particular classes.

before going on to justify the need of encouraging manufacturing particularly because other countries had done the same. The use of tariffs to support home industries grew dramatically in the 1800s and became one of the primary questions of political economy of the era. Proponents of protectionism argued that American industries needed assistance in getting started, that it would not do to simply import from Britain or Germany goods that the US should be learning to produce at home. The flaw in this reasoning, Henry George pointed out well in his work Protection or Free trade, comparing the idea that ‘we should keep our own markets for our own producers’ was akin to the absurd ideas that “We should keep our own appetites for our own cookery, or, We should keep our own transportation for our own legs.” Restricting the government market from importing goods, in such a case, was equivalent to robbing a person of their ability to enjoy the cooking over others, or, more dramatically, to avail themselves of a carriage or horse for their transportation. And this has generally been the Liberal position, pursued by Franklin Roosevelt, Bill Clinton, and many in between - lifting restrictions on trade so that American consumers could get cheaper products (and, importantly, so that American producers could get cheaper intermediate goods).

But government purchases have always been subject to special scrutiny, and since Trump’s successful 2016 campaign both parties have seemed enthusiastic to maintain or expand ‘Buy American’ provisions. The results have harmed our relations with neighbors and made our investments less efficient.

Hardly a costless provision

Canada, for one, has been understandably annoyed by Buy America provisions and other ‘America first’ policies. The country has gone so far as to warn that it may limit its own government procurement from American firms in response. Throwing up trade borders between nearby metropolitan areas such as Seattle and Vancouver or Detroit and Windsor makes little sense, but American policies have put the Canadian government in a difficult position; after all, what government wants to admit that the best path forward is to let their larger neighbor act with impunity? The inability of Canadian or Mexican leaders to show wins for their voters on this topic puts unnecessary strain on these relationships - a dark splotch in a bright relationship with Canada, and further burdens to an already difficult relationship with Mexico.

In addition to diplomatic costs, ‘keeping our own transportation for our own legs’ has gone beyond metaphor and created an impact on our own transportation policy. The provisions have been cited as a factor in rising costs of infrastructure projects, contributing to an already alarmingly poor record of cost control for transit projects in the US. Philip Rosetti, Jacqueline Varas, and Brianna Fernandez at the American Action Forum note that in the case of metro construction, “By refusing to take advantage of established global supply chains for metro cars, U.S. procurements for metro cars are merely paying a premium for the companies to open manufacturing locations within U.S. borders.” Similarly, Robert Atkinson at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation argues that the US IT industry is inadequately prepared to supply the needs of Buy America provisions in the Infrastructure and Jobs Act in an efficient way. And simply by adding another requirement to government procurement, these kind of provisions necessitate hiring more administrative and compliance staff, a cost in itself.

Ultimately, if ‘Buying American’ means getting fewer or lower quality goods, then government procurement - where those goods are ostensibly going to aid the public as a whole - is a uniquely inappropriate place to apply these kind of restrictions. American consumers may choose on their own to look for a ‘Made in the USA’ label when making purchasing decisions, but when the purchase is made by the government on their behalf, the priority should be delivering the best government services possible.

The arguments for Buy American…

There are, however, arguments that are not perfectly economic in nature that are used to defend these kinds of provisions. To continue George’s metaphor, one reason to save one’s own transportation for one’s own legs is to strengthen the legs in case alternative transportation is suddenly unavailable. This kind of strategic consideration is a common argument in favor of ‘Buy American’ provisions - if American industry doesn’t get support, we’ll be out of luck in the event that we lose access to our trade partners.

There are important examples of this. For example, Taiwan’s massive dominance of the semiconductor industry puts the US in a terrible position if that state is cut off from foreign trade by military intervention or some other event. For this reason, encouraging the development of a domestic industry, via direct subsidy or an indirect subsidy like ‘Buy American’.

Moreover, when government spending is used as countercyclical fiscal policy - policy designed to increase demand in the economy during recessions - Buy American might also make sense. Import leakage of stimulus dollars makes the stimulus less effective as fiscal policy, and might make major relief spending ineffective. This is certainly not a concern now, as inflation rises in a hot economy, but could have more merit in the case of traditional stimulus spending.

…are unconvincing.

However, countries with which the US shares a land border only potentially suffer from this problem of strategic disruption if direct conflict occurs between them and the US, or extreme unrest makes their industries unreliable. This is exceedingly unlikely with Canada, and the probability is also low with Mexico. This was shown during the early months of the COVID pandemic, when Mexican exports of ventilators to the US surged; later, the US would reverse the direction of sales and send ventilators to struggling Mexican hospitals.

Indeed, it is difficult to imagine a case where the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico are unavailable to American shipping, minus a collapse in American naval power that is on no one’s radar. There are of course questions of not wanting to grow dependent on states that could over time become unfriendly; Nicaragua and Venezuela present examples. But for the NAFTA countries, as well as many in Central America and the Caribbean, this is not a serious threat.

Moreover, the interconnectedness of the NAFTA economies means the idea of stimulus money ‘leaking’ out of the US is also a lot less concerning than it might be given a different country. US exports to Canada came to over $250 billion in 2021, over 1/8 of Canada’s total GDP; exports to Mexico were roughly the same, thus making up an even greater portion of GDP. To the extent that there is a fiscal multiplier effect to stimulus spending, even spending that is spent in Canada and Mexico is likely to redound into the US economy to some degree - and a multilateral agreement on government procurement between the three countries, and potentially more, could benefit them all.

Real life is more complex than an economic textbook, and so sometimes the perfectly free trade we might advocate in theory would be detrimental given the realities of business cycles and strategic industries. But this is not sufficient reason to cut our closest neighbors out of the US government procurement, especially as it is likely to be a substantial part of the economy as major climate change prevention and adaptation projects are required in the coming decades. A policy or, better still, multilateral agreement that included Canada, Mexico, and other friendly, nearby countries would be a major improvement over the current protectionist purchasing requirements.