Nuclear weapons cannot be used for aggrandizing blackmail

Down that path is only disaster

After the United States bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki using the atomic bomb in 1945, George Orwell wrote an essay about what that meant for the future of society. In “You and the Atom Bomb”, Orwell acknowledges fears of a cataclysmic war but also argues

"But suppose – and really this the likeliest development – that the surviving great nations make a tacit agreement never to use the atomic bomb against one another? Suppose they only use it, or the threat of it, against people who are unable to retaliate? In that case we are back where we were before, the only difference being that power is concentrated in still fewer hands and that the outlook for subject peoples and oppressed classes is still more hopeless.”

For the duration of the Cold War, the US and USSR retained such an agreement in practice, avoiding direct confrontation that could spiral into a nuclear war. However, on plenty of occasions his assumptions about the relationship between nuclear powers and non-nuclear states did not work out as Orwell expected - nuclear powers France and the United Kingdom were unable to keep ahold of their colonies, and the United States in Korea and Vietnam faced conventional military defeats without using nuclear weapons or the serious threat of them to get its way. And the USSR collapsed despite its nuclear arsenal.

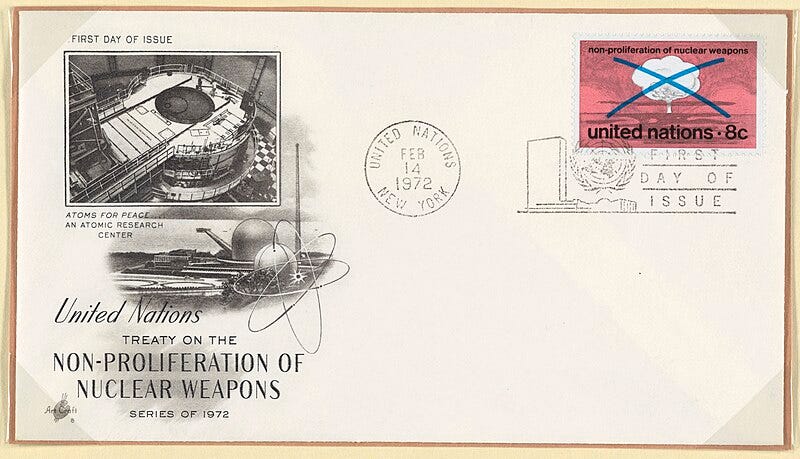

Although nuclear weapons were understood to hold conventional threats at bay, new norms developed along with them. The development of the United Nations set strong norms against the absorption and destruction of its members. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, agreed to in 1968, also operated on this assumption, with its finally preambulatory clause reading:

”Recalling that, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, States must refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations…”

The idea being that non-nuclear states would be protected by the modern, rules-based order and would thus have no reason to seek nuclear weapons. Incredibly, perhaps, this system worked. The US and USSR clashed over Korea and over Vietnam, and Soviet nuclear and conventional forces kept the US at bay as they invaded Hungary and Czechoslovakia, but they did not attempt to expand their territories by force in this period.

As the Cold War came to a close, the U.N. was presented with a very direct challenge to its principles as Iraq invaded and annexed Kuwait, a UN member. The UN, pushed by the United States, responded by authorizing a mission to expel Iraq from Kuwait and re-establish Kuwaiti sovereignty. The era of land wars seemed to be coming to an end - the results were too unpredictable, especially since most countries could call on allies to defend them or at least increase the cost of those wars substantially. American intervention in Iraq and elsewhere in the 2000s weakened this premise, but maintained the taboo on outright annexation.

However, this situation faces substantial challenges from two nuclear states, the Russian Federation and Israel. Both have long sought territorial expansion through conquest - places like East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, or Transnistria and South Ossetia - but now threaten much more dire consequences. Russia has, despite its obligations under the Budapest Memorandum, has invaded Ukraine and now seeks to annex, in whole or in part, four oblasts thereof. Since the finalization of these annexations, Russia has stepped up its nuclear blackmail, threatening (through former President and current Deputy of the Russian Security Council Dmitri Medvedev) the use of nuclear weapons if assistance from NATO countries allows Ukraine to succeed in taking back its de jure territories - and there is little doubt that fear of exactly that sort of escalation has impacted western countries’ willingness to act. It certainly was a driving force behind their acceptance, nearly a decade ago, of Russia’s annexation of Crimea - a clearly illegal act nonetheless accomplished without any kinetic pushback.

Russia has made its goal of annexation clear. Israel has been more opaque with its intentions towards Gaza - it’s unclear that even the Israeli government itself knows what it intends to do with the territory. Members of the Knesset are, however, openly discussing the removal of the local population, and Benjamin Netanyahu’s own statements do not clarify who he thinks should run Gaz

a. But in this case too it is clear that Israel is leaning not just on their conventional military but on a nuclear deterrent to deter any kind of intervention in Gaza.

Both situations present a challenge to the United States. There is little that can be directly done about Russia except to continue to arm Ukraine and make clear that as long as any Ukrainian territory is annexed, Russia will be ostracized and hit with the most damaging sanctions practical. A failure to act decisively before the invasion or in its early stages have made it very difficult to avoid conceding land in the face of nuclear blackmail - a crippling blow to the international order and especially to non-proliferation.

In the case of Israel the US has, probably, more leverage. Biden has submitted a request for aid to Israel that would be a substantial addition to the Israeli military budget - $14 billion representing something like 2/3 of the total budget. Well used, this is a carrot. The stick could come with ceasing the current policy of defending Israel in the UNSC, or even withdrawing the naval units currently intercepting missiles and drones aimed at Israel. Whatever leverage the US has needs to be used to set a precedent that nuclear powers cannot use that blackmail to keep intervention at bay and engage in military land grabs or ethnic cleansing - which means demanding the Gazans be allowed to return to their homes and that a new civil administration run by Gazans themselves take control with the withdrawal of Israeli troops.

Orwell may be correct that the nuclear age is fated to be dominated by just a few states with the capacity to build these weapons. However, this will become much less tolerable (and thus, non-proliferation much harder to maintain) if these powerful states begin seizing land from their neighbors through nuclear blackmail. The United States should seek to use the tools at its disposal with respect to both Russia and Israel to try to rebuild and fortify this norm - any other direction leads to a much darker world.