There is no 'realist turn' in Republican politics

Vance is no more a realist than Trump, and may somehow be less principled

JD Vance is on track to be among the least possible Vice Presidential picks in recent memory, and for good reason - his social views on abortion and more generally the role of women and reproduction would, one would think, be disqualifying in an election defined by the end of Roe vs Wade. But he has his defenders - most famously, in Silicon Valley, where oligarchs like Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, and David Sacks lead a reactionary cohort that seeks less regulation of technology domestically and a rapprochement with Russia in foreign policy. Sacks and Musk in particular have long pushed the idea that American involvement in Ukraine risks a wider war, and that Ukrainian sacrifice of territory should be encouraged (read: coerced) by US foreign policy.

Shoring up this vision of the world, The American Conservative hailed Vance’s appointment as a “Foreign Policy Realist”. The word ‘realist’ is of course carefully chosen. Something like the “reasonablists” of Parks and Recreation whose name makes disagreement with their absurd millenarian beliefs immediately sound unreasonable, ‘Realists’ enjoy the title that makes the rest of us seem somehow separated from reality. It’s thus an attractive title - but not one that fits Vance, even on its own terms.

The idea that the aggressor states of the world are of no real concern to us on the American continent is certainly not a new one. When Franklin Roosevelt delivered his “Quarantine Speech”, he largely laid out the opposing, liberal view - that

…if we are to have a world in which we can breathe freely and live in amity without fear—the peace-loving nations must make a concerted effort to uphold laws and principles on which alone peace can rest secure. The peace-loving nations must make a concerted effort in opposition to those violations of treaties and those ignorings of humane instincts which today are creating a state of international anarchy and instability from which there is no escape through mere isolation or neutrality.

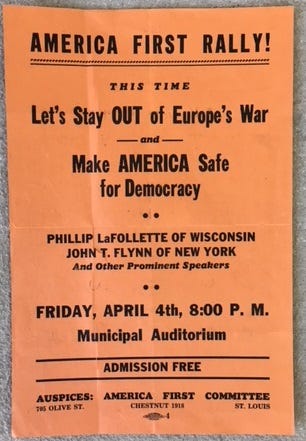

This speech earned Roosevelt animosity from isolationists, including major newspapers and the America First Committee. These of course failed to keep the US out of the war, and isolationism as a politically influential doctrine lost most of its influence. However, this doesn’t mean that Roosevelt’s liberalism won out - instead, realism as a doctrine of international relations arose to challenge many liberal assumptions. Hans Morgenthau’s book Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace is seen as the seminal work for this perspective on international relations, though Morgenthau drew from older ideas from thinkers like Machiavelli and Hobbes. The idea was to be clear headed and unidealistic about how international politics works, and the result was an emphasis on power and security, defined in strictly amoral terms, as the overarching goals of both war and diplomacy.

The most prominent proponent of foreign policy realism today in the US is almost certainly John Mearsheimer, whose 2001 book The Tragedy of Great Power Politics is a must-read text for modern international relations theory. In addition to the basic principles of realism advanced immediately following World War II - that states are the primary actors in an anarchic global system, that their primary concern is security, and that the unpredictability of state behavior means only power can maintain security - Mearsheimer asserts the importance of a “counter hegemony” or “offshore balancing” model. There are serious problems with Mearsheimer’s scholarship, which I’ve gone into before: the most glaring being that states don’t seem to behave the way he predicts, and he has to fudge the historical record to pretend that they do. But we can safely take Mearsheimer as a prime example of realism in American international relations discourse today and see if the current Republican ticket lives up to it.

Counter-Hegemony in Theory

Offshore balancing and counter hegemony are based on the idea that oceans are powerful barriers to the deployment of military power, and thus it is effectively impossible, as well as unnecessary, to be a global hegemon (a state of unrivaled power in any part of the world). Instead, states need strive only for regional hegemony, dominance of their immediate landmass, and countering the potential creation of other regional hegemons. Thus, World War I was fought by England to prevent the rise of a German hegemon in Europe, and World War II in the Pacific was fought by the US to prevent the rise of a Japanese hegemony in East Asia. The United States, blessed as it is with broad oceans on either side (and, though Mearsheimer would argue these are unreliable, good relations with its neighbors), is easily a regional hegemon. The only fear it faces is that another regional hegemon will arise that can both dominate its own sphere and make alliance to interrupt our hegemony in our own. This means countering the potential power of any regional hegemon that might arise in the Middle East, East Asia, or Europe and Russia (other regions being, at present, less economically powerful).

Russia and China are the only reasonable hegemons to consider in this way of thinking. While the European Union is dramatically wealthier than Russia, it lacks a nuclear arsenal on a Russian scale, and even in conventional weaponry was likely lagging prior to the war in Ukraine. This, along with Russia’s immense natural resources, makes it a potential hegemon in Europe despite its relatively small population and unproductive workforce. China by contrast is a truly massive state, the first in over a hundred years to be a true economic match for the United States. Given the concentration of the global population in East and Southeast Asia and the rapid rate of capital construction there, China’s ability to dominate the region would, in Mearsheimer’s view (which for once is likely accurate) constitute at least a potential problem for US security. This is likely to occur in the future if there is a conflict in which China forces Taiwan, South Korea, or Japan to make any substantial sacrifice of territory or autonomy. In the Middle East, there is no potential hegemon. Egypt is populous but poor, and its military has a poor record of success in anything except controlling the country. Israel is the opposite - wealthy and with a highly efficient military, but without a population base to support regional hegemony (not to mention huge ideological barriers to cooperation with its neighbors). And Iran, though much feared, has shown itself mostly incapable either of directly striking Israel or offering any substantive protection to its proxies in Lebanon or Yemen. Thus, we can saw the Middle East is fundamentally a well-balanced situation, geopolitically speaking (this does not mean stable, and indeed a rough balance of power often spells tragedy for the people of a region caught between rival powers, but these things do not concern realists). In none of these three regions does Vance represent a counter-hegemony perspective.

Allowing a Hegemon in Europe

In Europe, Vance has indeed followed Mearsheimer’s advice in downplaying the importance of Ukraine, but here Mearsheimer’s analysis is fundamentally flawed. As Mearsheimer himself knew in writing Tragedy, Russia was always a potential hegemon if its economy recovered from the post-Soviet collapse. It has now more than done so, on the back of surging fossil fuel demand. Russia’s economy may not be nominally as powerful as those of the countries west of it, but it is self sufficient in most important resources, unlike Europe. Moreover, Russia had, before its invasion of Ukraine, a stockpile of tanks, artillery, and munitions for both that dwarfed anything on the European continent, and the industrial capacity to supply its army with shells far in excess of what Europe could ever match. And Europe’s great industrial power, Germany, is decidedly *not* a nuclear power; given that it lacks even nuclear power plants, it is unlikely to become one in the future.

All of this indicates that Mearsheimer’s early 2000s prediction that either Germany or Russia would be a future hegemon in Europe was close to correct, but that there is in fact no real competition between the two. In a decade, when Putin is likely dead and fossil fuels are hopefully less crucial to the European (and perhaps global) economy, this may shift (especially if Russia’s stockpiles of conventional weapons are depleted in Ukraine). But until then, Russian control over Eastern Ukraine, especially industrial centers like Kharkiv and Dnipro, would be a disaster for the European balance of power, and it’s entirely contrary to a counter-hegemonic position to claim ‘not to care’ about Ukraine.

A Fully Ideological Commitment to Israel

By contrast with his “America’s shortest possible term interests first” stance on Ukraine, Vance absolutely abandons Realism in his consideration of Israel, saying this year that ““A majority of citizens of this country think that their savior, and I count myself a Christian, was born, died, and resurrected in that narrow little strip of territory off the Mediterranean. The idea that there is ever going to be an American foreign policy that doesn’t care a lot about that slice of the world is preposterous.”

Neither Vance nor Trump has proposed any limits to American support for Israel, and both seem dedicated to seeing the US support Israel’s military conflicts throughout the region. There is no real counter-hegemonic argument for this stance, however. Israel is not a necessary counter to Iranian influence - indeed, it is uniquely ill suited to that purpose. The biggest obstacle to Iranian hegemony in the Middle East is mistrust between the Sunni Arab majority in most countries there and Iran’s Persian Shia leadership. But antipathy towards Israel cuts straight across these divisions and makes it more difficult for the US to prop up any actual opposition to Iranian expansionism, and constantly running diplomatic cover for Israel isolates the US from potential allies in the UN and elsewhere. Moreover, US military aid to Israel cuts into supplies available for any other country - like Ukraine. All of this done without even a feigned realistic motivation!

A Shallow ‘Pivot’ to Asia

Many Realists have argued the US needs to pivot to the Asia-Pacific region, even if it means abandoning some commitments in Europe. This is one way Vance could justify his desire to abandon Ukraine. But he doesn’t seem to have support from the Republican party in managing this. The official Republican Party Platform in 2024 removed any mention of Taiwan - for the first time in decades. Moreover, Trump has taken to discussing Taiwan in largely the same tones he discusses NATO, claiming that Taiwan should ‘pay us’ for its defense, in much the way he pushed a rather nonsensical claim about NATO countries failing to pay their ‘bills’. Vance may argue that US foreign policy should be focused on countering China, but his party seems to have missed the memo.

And it seems increasingly unrealistic to try to disentangle Europe from East Asia. Russia is now receiving North Korean military supplies and has economically survived a punishing sanctions regime with assistance from Chinese firms. The dream of turning Russia against China never made particularly much sense, from a Realist perspective. China and Russia complement one another strategically, with Russia boasting massive reserves of raw materials and a cutting edge arms industry that feed and draw from China’s unmatched manufacturing capacity. Russia’s military occupations of Georgia and Moldova, both dating from before any NATO expansion East, showed a longstanding unwillingness to abandon its imperial goals - and Russia had basically no reason to turn against China, given that it was and is incapable of incorporating Chinese territory into itself or otherwise gaining from such a venture. This is probably why the Foreign Minister of Taiwan himself, Joseph Wu, has come out in favor of defending Ukraine as a means of defending Taiwan in the future.

Harris is the Only Reality-Based Candidate

If the last eight years are any guide, the vast majority of conservatives will, enthusiastically or skeptically, end up supporting the Trump/Vance ticket. A jubilant vote of course counts for just as much as a clothespin vote, so expect plenty of Trump-friendly media to try to explain Vance’s foreign policy stances, especially those opposed to Ukraine, as part of a novel Realist strategy. Some will no doubt go so far as to paint remaining Ukraine supporters or ‘National Security voters’ as hopeless idealists still locked in a ‘neo-con’ mindset. But even following the basic principles of Realistic international relations theory, Vance’s positions on Europe and the Middle East are fundamentally backwards, and his hawkishness on Asia is shallow and unsupported at the top of the ticket where it matters. This year, from both a Realist and Liberal international relations perspective, only Kamala Harris presents a defensible choice for president.