To prevent violent disruption, campuses should allow more peaceful inputs in governance

At least, if they want to continue to be a unique kind of institution

Campuses around the country are seeing an increase in protests and occupations demonstrating against Israeli violence towards Palestinians, American complicity in that violence, and most acutely their universities’ own financial ties to Israel. The situation is rapidly developing and will likely look different when you read this compared to as I write it, but the broad outlines are as old as civilization itself. Members of a group have a series of demands - some abstract perhaps but others quite concrete, particularly divestment from Israeli firms.

Multiple dynamics are at play in the current round of clashes - concerns about antisemitism balanced against a right to criticize and condemn the behavior of the state of Israel; the desire of Republicans to find electoral an electoral issue to use against Biden, intersecting with the intraparty, and frequently intergeneration, conflict between supporters and opponents of Israel within the democratic party. But on at least on the level of the question directly confronting universities, it seems the question is fundamentally down to what kind of institutions, and indeed, what kind of communities they want to be.

The Options

One option of course is to operate as institutions with direct authority over faculty and students - particularly private universities that are at least partially independent from state governments that dictate the behavior of public universities. In this way they would operate essentially as businesses - with property and shareholders and effectively ‘at will’ relations with their ‘employees’ and ‘clients’. In this conception, the university is at least legally justified in removing unruly customers from their own property - thought the appropriateness of utilizing legions of police officers and provoking violent confrontations to enforce a trespassing restriction is debatable.

But there is a reason this seems less than satisfying. Universities as institutions were not founded on the same basis as companies or corporations. The spirit of universities is fundamentally different, built at least in theory around the institution of academic guilds, where students and professors share a common goal of pursuing the truth in a spirit of collegiality. Giving university administrators the power to reject students that corporate executives can alienate customers seems to undercut precisely what makes the university such a sort of institution - one that is in fact a community.

And not just any community, but one peculiarly well-educated and engaged with the world around them, and their own university communities. This engagement, however, is not matched by real voice within the institutions that define their lives (and take most of their money). It seems evident that the problem is at least partially the lack of a formalized voice with real impact on policies within the university.

A Liberal Perspective

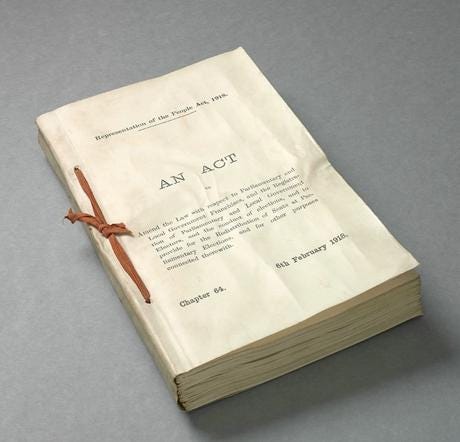

In 1911, as the United Kingdom and indeed Western world were grappling with the implications of truly universal suffrage, LT Hobhouse wrote that “The success of democracy depends on the response of the voters to the opportunities given them. But, conversely, the opportunities must be given in order to call forth the response. The exercise of popular government is itself an education.” Universities cracking down on student protest clearly feel that their students’ demands are irresponsible or unrealistic. If we grant that this is so, perhaps that is precisely because the demands have no formal mechanism for gathering popular support and becoming reality. Hobhouse suggests that in granting the franchise, society asks of a particular class, “Would it enter effectively into the questions of public life”, but warns that many are quick to assume that various classes of people would not, without considering how the capacity to exert real political power can awaken political consciousness and inspire greater political participation. Too often, authorities looking to limit democratic input are “apt to overlook the counterbalancing danger of leaving a section of the community outside the circle of civic responsibility.” If university administrators believe their students to be acting in a civically irresponsible matter, they should consider perhaps that it is because they are insufficiently invited into the circle of civil responsibility.

This is all the more true if universities believe that the occupy camps and protestors are a vocal minority. Hobhouse notes that “The ballot alone effectively liberates the quiet citizen from the tyranny of the shouter and the wire-puller.” Inviting actual student democracy on key questions - for example, the divestiture of university assets from Israeli firms - would open up new avenues for student communication with administrators. It would allow a broader spectrum of voices, encourage more nuanced and in depth debate, and remove any feelings of ‘unsafety’ experienced by students adjacent to protests. It would also remove any question as to a ‘vocal minority’ or ‘outside agitators’, assuming the university is halfway competent at running a plebiscite.

Of course, this may be precisely what university administrators fear - that they are dealing with deep dissatisfaction from their most important stakeholders, the students. Even then, formal mechanisms like elections and petitions are crucial to keep administrators informed and allow the university to function as a true community of students and faculty seeking and creating knowledge.

This isn’t the only path available to universities, of course. They can choose to operate like businesses and relegate faculty and students to that of employees and customers, respectively. But such a path would abandon much of what has made the centuries long university tradition a unique one in the western world. Moreover, if student and faculty occupations of university property come down to a dispute between labor, customers, and management, it’s unclear that cities and states are justified in putting their policing resources into resolving them, and conversely quite clear that police and the criminal justice system are ill suited what is really a question of commercial arbitration.

From my perspective, admittedly many years out of academia, it seems that utilizing this potential crisis as an opportunity to expand student democracy would be a far more fruitful path. Hobhouse is correct - having more formal input into decision making is an education in itself. It would encourage student bodies to become more responsible, and push activist organizations to put forth concrete and realistic proposals. A student body plebiscite on, for example, divesting from particular companies would have a legitimacy that management negotiating with protestors lacks. And probably nothing would prepare students better for their responsibilities as citizens of the broader community that giving them more active and official roles in university governance.